A Lament of Leaving When Heartache Won’t Let You Stay

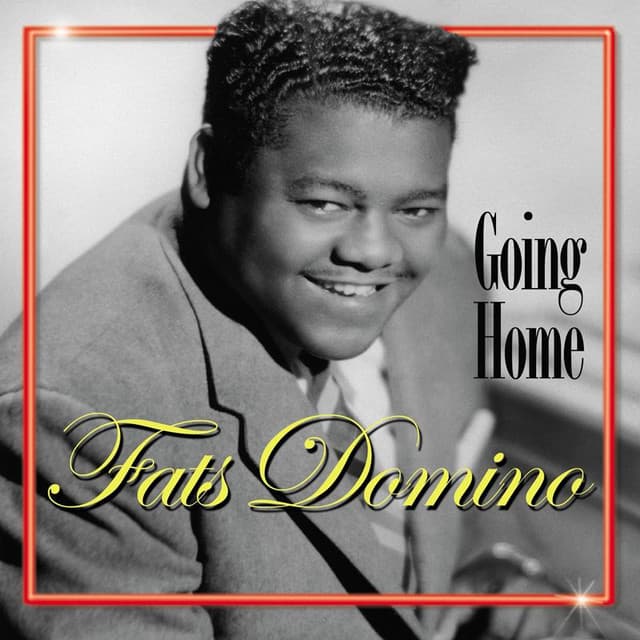

In March 1952, Fats Domino released “Goin’ Home”, co-written with Alvin E. Young and produced by Young for Imperial Records. That single marked a watershed in his career — it became his first #1 on the U.S. Billboard Best-Selling Rhythm & Blues chart, climbed to No. 3 on the Most Played Juke Box R&B chart, and even broke into the pop ranks, reaching No. 30 on the broader Hot 100. It was later included on his first compilation album, Rock and Rollin’ with Fats Domino (1956).

From the first mellow piano notes to Domino’s plaintive, slightly quivering voice, “Goin’ Home” carries the weight of a man torn between bitterness and retreat. On the surface, it reads as a breakup song: the narrator insists he’s leaving because he “can’t stand your evil way,” pleading for no calls, no attempts to reconcile, asserting he’ll be “better off without you.” But in Fats Domino’s hands, those words resonate with more than romantic heartbreak they pulse with the ache of displacement and the longing for sanctuary.

According to biographical commentary, Domino and his bandmates were homesick for New Orleans while they recorded in an era when many Black Americans were leaving the South. The repeated refrain “Goin’ home tomorrow” becomes more than just a declaration of escape — it stands as a promise of return. Home here is not just a lover’s embrace, but a refuge: a place of belonging away from misery, alienation, and “evil ways” that may well echo the broader social pressures of the early 1950s, including segregation and migration.

Musically, the song is deceptively simple: built around a piano riff in C major, with classic R&B chord movements (C, F, G7) that anchor Domino’s weary but resolute voice. The structure—a melancholic verse leading back to that hopeful, yet rueful refrain—mirrors the emotional tug-of-war in the lyrics. It’s not a wail of despair; rather, it’s a controlled cry, as if he’s holding himself together long enough for one final, dignified exit.

What gives “Goin’ Home” its enduring power is this tension: Domino’s singing often cracks, his voice trembling just at the edge of grief, but he never fully breaks. As noted by music commentators, there is a dramatic quality in how he delivers lines like “I can’t go on this way” — he flirts with sobbing, yet restrains himself, embodied in the repetition that feels like both confession and affirmation.

In the cultural context, the song became more than a hit — it resonated with people far beyond romantic sorrow. For those migrating away from the South, or soldiers stationed far from home, its simple promise of “going home tomorrow” felt deeply personal. That emotional universality helped cement the song’s legacy, and it influenced generations of R&B and rock artists.

Over time, “Goin’ Home” has been honored repeatedly — not least in the 2007 tribute album Goin’ Home: A Tribute to Fats Domino, whose title itself underscores how central this song remains to his body of work. In that light, the track is more than a farewell — it is a homecoming, both in spirit and in sound, a declaration that in leaving, one might also find return.

For Fats Domino, that bittersweet declaration of departure became a milestone: his first chart-topper, his poignant emotional statement, and one of many songs that remind us of the power of roots, memory, and the longing that shapes the human heart.