Meeting of Two Honky-Tonk Souls, Where Heartache Finds Its Harmony

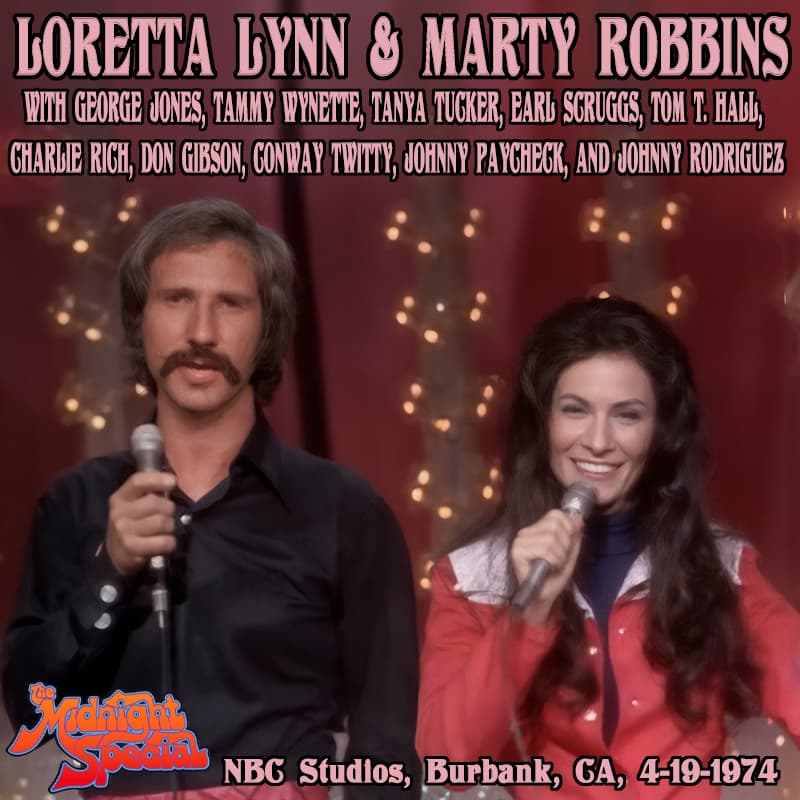

On August 24, 1973, American television audiences watching NBC’s The Midnight Special witnessed a rare convergence of country royalty: Loretta Lynn and Marty Robbins standing shoulder to shoulder to deliver “Singin’ the Blues.” Though the song itself first became a country standard in the 1950s—most famously a No. 1 country hit for Robbins in 1956 and later a pop crossover success—this duet performance was not about chart positions or commercial ascent. It was about legacy. By 1973, both artists were firmly established titans: Robbins with a career defined by narrative ballads and Western epics, and Lynn reigning as one of country music’s most vital and defiant female voices. Their meeting on a national late-night stage was less a promotional stop and more a ceremonial reaffirmation of country tradition.

Originally written by Melvin Endsley, “Singin’ the Blues” is deceptively simple in construction. Its lyric sketches a familiar emotional terrain: the wounded lover, the restless heart, the ache that hums just beneath the surface of daily life. Yet in Robbins’ hands, the song in 1956 carried a buoyant rhythm that softened the sorrow, giving heartbreak a melodic swing. When he revisited it in duet form with Lynn nearly two decades later, the composition gained an added dimension: dialogue.

Lynn’s presence alters the emotional geometry of the piece. Her voice—earthy, unvarnished, forged in Appalachian coal country—does not merely echo Robbins; it answers him. Where Robbins projects a polished melancholy, Lynn introduces lived-in resilience. The blues here are no longer a solitary confession but a shared condition. This is not despair wallowed in isolation. It is heartache recognized, acknowledged, and harmonized.

By 1973, country music itself was in transition. The Nashville Sound had smoothed many of the genre’s rough edges, while outlaw currents were beginning to stir beyond Music Row’s polish. Against that backdrop, this performance feels almost archival in spirit. Two artists who had each defined different facets of country’s golden era step forward not to modernize the song, but to preserve its emotional core. The arrangement remains straightforward, anchored by steady rhythm and clean melodic lines. The power lies not in embellishment but in interplay.

Watching them trade lines, one senses mutual respect more than theatrical dramatics. Robbins, ever the gentleman stylist, frames his phrases with precision. Lynn counters with instinct. The tension between refinement and rawness becomes the performance’s quiet electricity. The blues, in this context, are less about spectacle and more about authenticity.

In that studio light on The Midnight Special, “Singin’ the Blues” ceased to be merely a mid-century hit and became something richer: a bridge between eras, between masculine croon and feminine candor, between memory and endurance. It reminds us that in country music, sorrow is rarely silent. It is sung—sometimes alone, sometimes together—but always with the conviction that harmony can steady even the heaviest heart.