The Quiet Pain of Departure and the Fragility of Love in TOMORROW YOU’LL BE GONE

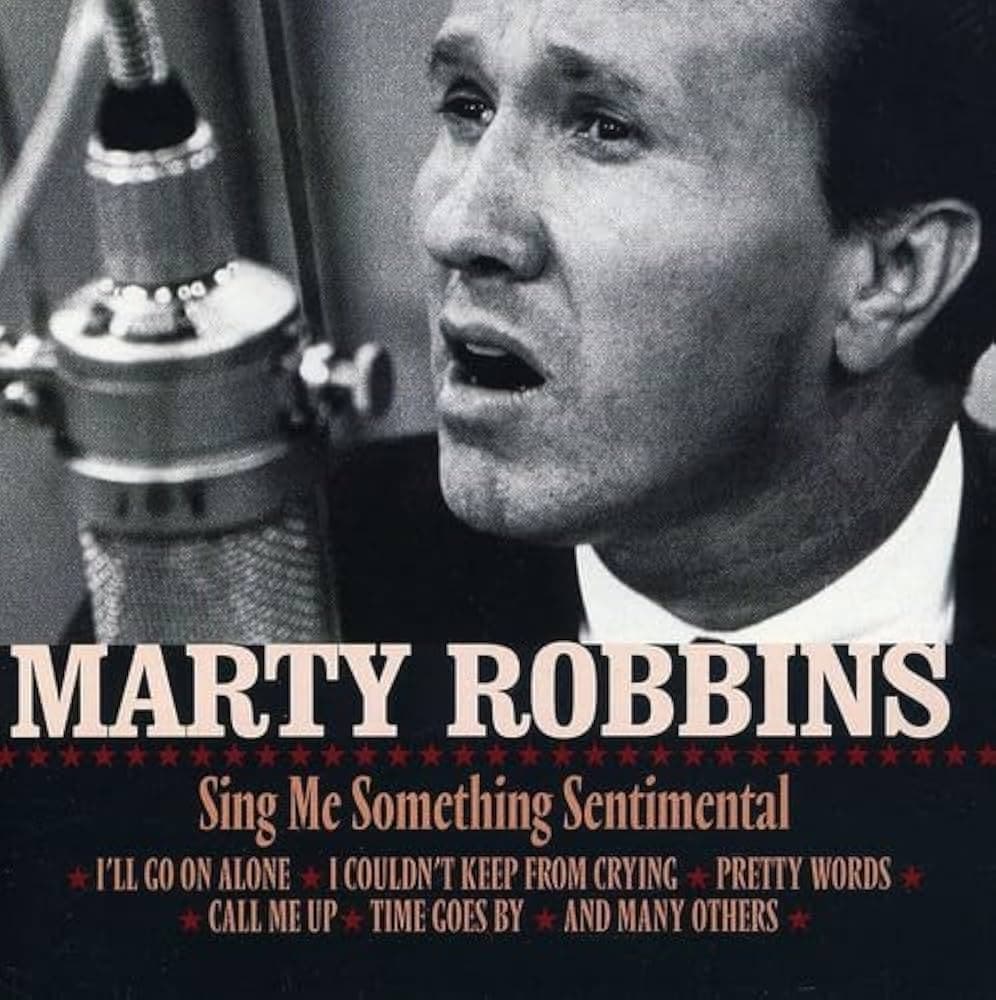

Tomorrow You’ll Be Gone is one of the earliest recordings in Marty Robbins’ storied career, originally released in 1952 as the B‑side to his single Love Me or Leave Me Alone on Columbia Records. This poignant ballad did not climb the charts as Robbins’ later hits would. Indeed, like many of his early “weeper” tunes, it failed to register on Billboard’s country listings at the time. Yet even without chart success, the song endures in retrospective compilations such as The Essential Marty Robbins 1951‑1982 and A Lifetime of Song (1951‑1982), preserving its place within the deep catalogue of Robbins’ formative years.

From his first sessions with Columbia in Hollywood in late 1951, Robbins was at heart a storyteller. He soon demonstrated a remarkable ability to encapsulate human longing and sorrow within the compact frame of a traditional country ballad. Tomorrow You’ll Be Gone epitomizes this early phase of his artistry, where spare arrangements and heartfelt lyricism were paramount. Robbins’ vocals, already tinged with his signature smoothness and emotive resonance, navigate the song’s terrain of imminent heartbreak with an intimacy that feels confessional rather than performative.

The lyrics unfold like a whispered lament to lovers and listeners alike. Robbins does not dramatize loss with sweeping gestures. Instead he dwells in the quiet spaces where heartache lingers: the moment before departure, the heavy inhale of a final farewell, and the fragile hope that perhaps love might endure beyond its apparent end. Lines such as “Tomorrow you’ll be leavin’ and I’ll stand and watch you go” capture the vulnerability of someone caught between denial and the bleak clarity of impending solitude. This is a love song that acknowledges its own futility even as it clings to the possibility of reunion.

Musically, Tomorrow You’ll Be Gone reflects the aesthetic of early 1950s country music. The arrangement is unobtrusive, leaning on acoustic textures that foreground Robbins’ expressive phrasing. Such simplicity is not a limitation but a deliberate choice that amplifies the emotional core. In the wider context of his career, this early ballad stands in contrast to the Western epics (El Paso) and rockabilly‑tinged numbers that would later define Robbins’ mainstream success. Yet it is precisely here, in these quieter songs, that the depth of his empathy and his intuitive grasp of human vulnerability first emerge.

Though it never garnered commercial acclaim in its own time, Tomorrow You’ll Be Gone remains an evocative testament to Robbins’ early craftsmanship. It offers listeners a glimpse into the artist’s foundational commitment to poems of loss and love, where every note and syllable seems weighted with personal history. In the vast mosaic of Robbins’ legacy, this song is one of the earliest threads woven through a lifelong exploration of the human heart.