A Quiet Resolve That Turns Heartbreak Into Hope

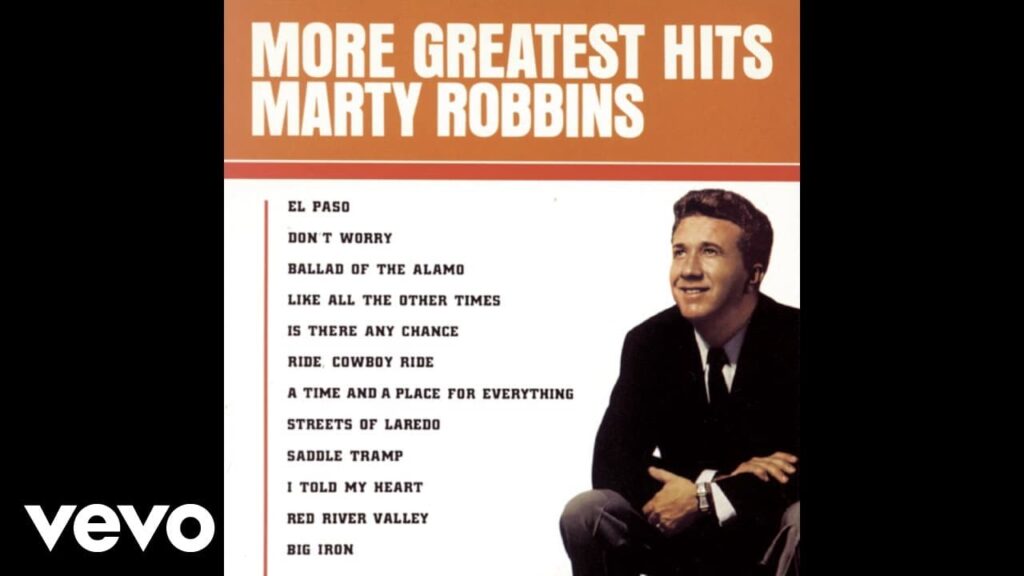

In the spring of 1961, Marty Robbins’ tender, introspective ballad “Don’t Worry” emerged not merely as another country single but as a profound emotional statement that resonated deeply across divides of genre and audience. Issued as a single from the compilation album More Greatest Hits, the song ascended to the summit of the country charts where it remained for an extraordinary ten weeks and crossed over to reach number three on the Billboard Hot 100, a rare achievement for a country artist in that era.

From the first strains of acoustic guitar and Robbins’ calm, measured vocal approach, “Don’t Worry” feels like an intimate conversation delivered at dusk after a long day’s travel. It is not a bombastic lament screamed into the void but rather a restrained meditation on heartache and self-sacrifice, a declaration of emotional maturity at a moment when so many songs would choose melodrama. Robbins, already celebrated for his narrative craftsmanship in western ballads like “El Paso,” channels that same storyteller’s sensibility here into something quieter yet no less compelling.

At its core, “Don’t Worry” is a study in emotional generosity. The narrator, confronting the end of a relationship, does not plead or protest but instead insists upon the partner’s peace of mind even as his own heart sinks. Lines like “Don’t worry ’bout me, it’s all over now / Though I may be blue, I’ll manage somehow” unfold not as platitudes but as the profound reckoning of someone who has truly absorbed loss and chosen connection over self‑pity. This gesture of putting another’s comfort above his own suffering gives the song an enduring, almost spiritual resonance.

Musically, the recording holds a subtle but significant place in the history of 20th‑century sound. Session guitarist Grady Martin inadvertently introduced a gritty, distorted tone during the recording sessions when a preamplifier malfunction colored his instrument’s timbre. Instead of erasing this unexpected texture, Robbins and producer Don Law embraced it, weaving it into a bridge that enriches rather than distracts from the song’s emotional core. This choice stands as an early commercial use of what would become known as the “fuzz” sound, a sonic signature that would later permeate rock and roll and popular music more broadly.

The cultural impact of “Don’t Worry” is inseparable from Robbins’ own persona: a singer who carried the weight of lived experience without theatrics, whose voice could evoke dust‑blown plains as convincingly as it could cradle a wounded heart. Its chart success in 1961 signaled not only Robbins’ commercial peak but the moment when country music’s emotional subtlety found a broader audience, proving once again that the genre’s greatest power lies not in spectacle but in sincerity.

Over the decades, listeners have returned to “Don’t Worry” as a touchstone for reflection, a reminder that letting go need not be synonymous with despair. Its legacy persists in the way it models grace under pressure and offers solace without sentimentality. In the annals of Robbins’ storied catalog, this song remains a testament to his artistry: that sometimes the most profound expressions of love are the ones spoken softly, almost to oneself, yet heard by many.