THE RAGING DECLARATION AGAINST CONFORMITY AND SILENCING IN ROCK MUSIC

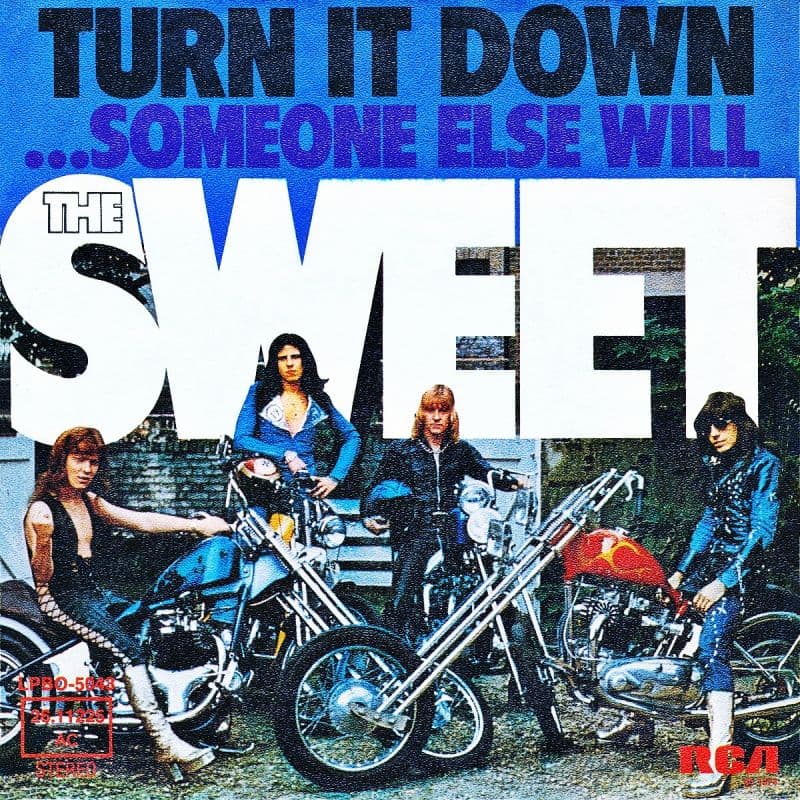

When Turn It Down emerged in late 1974 as a single by The Sweet from their third studio album Desolation Boulevard, it carved out an uneasy place in the band’s legacy. Released on 1 November 1974, the track reached number 41 on the UK Singles Chart, a modest placement that belied its ferocity and cultural resonance at the time. In continental Europe it found a more receptive audience, climbing into the top five in countries such as Norway and Germany, even touching number 2 in Denmark, before becoming a concert staple for devotees of hard-edged glam rock.

In the landscape of mid-1970s rock, Turn It Down stands as an unguarded roar against pressure to normalize and domesticate rock music. The Sweet were then navigating a critical transition. Originally associated with bubblegum pop and flamboyant glam stylings engineered in part by the hit-making songwriting duo Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman, the band began to push back, embracing grittier textures and themes that mirrored their evolution as musicians and commentators within the genre. While Turn It Down was penned by Chinn and Chapman, its sonic intensity and lyrical defiance foreshadowed the heavier trajectory that the group was stepping into.

From its opening guitar assault, the song refuses to apologize for its volume or urgency. The refrain itself — an almost literal invocation to “just turn it down” — refracts a duality common in rock music at the time: on one level it dramatizes the antagonism between youthful expression and establishment sensibilities; on another it satirizes the very notion of restraint in a culture that was just beginning to understand rock’s transformative power. Lines like “I can’t take no more of that God-awful sound so for God’s sake turn it down” place the “critic” within the song as both a literal character and a symbol of resistance to creative energy that cannot, and will not, be domesticated.

Musically, the track is steeped in the harder edges of glam rock. Where earlier Sweet singles often juxtaposed catchy pop melodies with theatrical production, Turn It Down embraces a leaner, more visceral sound. The guitars edge toward proto-metal crunch, and the rhythm section’s drive recalls a live stage energy unfiltered by studio gloss. This aesthetic choice aligns the song with a broader shift in the band’s repertoire and the rock milieu of the time — a push toward authenticity and sonic boldness that resisted radio sanitization and conventional expectations.

The song’s reception underscores a paradox that many boundary-pushing works encounter. In the UK, where the BBC reportedly curtailed airplay due to the perceived abrasiveness of certain lines, Turn It Down faced institutional resistance even as it garnered acclaim elsewhere. In continental Europe, listeners embraced its raw declaration, propelling it up the charts and embedding it into rock radio rotations. Its mixed chart fortunes thus function as a commentary on divergent cultural landscapes — where one market balked at its candor, others celebrated its unabashed force.

Yet beyond statistics and controversies, Turn It Down remains significant for its unabashed stance. It encapsulates an era in which rock music was wrestling with its own identity — between spectacle and substance, between noise and expression. In this tension lies its enduring appeal: a track that does not merely ask to be heard, but demands acknowledgment of rock’s capacity to disturb, invigorate, and defy.