A yearning confession sung under the New Orleans street-lamps

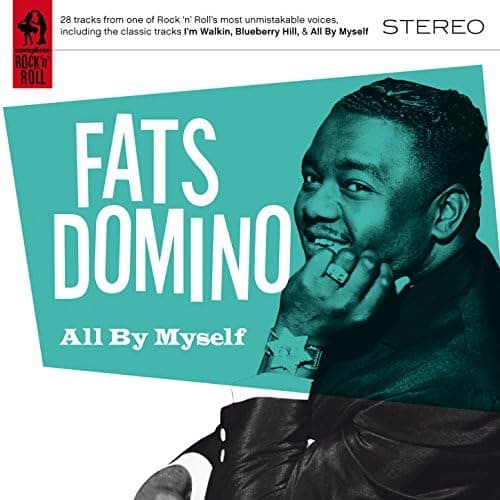

When All By Myself slipped from the scratchy grooves of 1955, performed by Fats Domino and included on his debut LP Rock and Rollin’ with Fats Domino, it quietly soared to No. 1 on the R&B charts — a modest triumph perhaps overshadowed by crossover pop hits, yet a defining moment in Domino’s ascendant reign.

From the first rumble of his piano to the croon of his voice, All By Myself feels like a midnight confession: solitary, insistent, and tinged with desire. In the broader tapestry of Domino’s emergence — amid the up-tempo shockwaves of songs like Ain’t That a Shame — this track stands out not for showmanship but for intimacy. It carries the husky weight of longing in every note, undiluted by pop-chart ambitions.

The Sound of a Heart Alone, Yet Full

Recorded during the same fertile 1955 session that produced “Ain’t That a Shame,” “All By Myself” captures a turning point. Domino, already a seasoned pianist rooted in the blues and boogie-woogie traditions of New Orleans, began to crystallize what would become his signature blend: a two-beat piano groove that’s both steady and swinging, underpinned by subtle syncopation.

This rhythmic foundation — neither straight blues nor polished pop — gives “All By Myself” a restless energy. The piano pulses with an easy confidence, while the saxophone solo slices through the texture with an earthy, human plaint. The arrangement refuses to smooth out discomfort: there’s tension between light and shadow, between the promise of companionship and the ache of solitude.

Domino’s vocal delivery is deceptively casual, almost conversational: “Little girl, don’tcha understand — I wanna be your makin’ man, all by myself…” Yet it carries a knowing weight, as if the speaker has already tasted disappointment but still hopes — still wants. In that soft insistence, the song becomes less about boasting or swagger, and more about vulnerability.

Lyrically, “All By Myself” flips the script on romantic inevitability. There’s no pretense of grandeur, no lofty declarations of undying love. Instead, Domino offers a raw, human need: “I don’t need no one else to love you — gonna love you all by myself.” It’s a straightforward pledge, but in its simplicity lies its power. The repeated invocation of “all by myself” becomes not a lament but a defiant claim — the narrator stakes his own identity, his own longing, on the truth of his voice.

A Quiet Rebellion — and Its Legacy

In the context of 1955, when segregation long dictated who heard what on the radio, the fact that “All By Myself” (and other tracks) topped R&B charts but largely missed the pop listings speaks volumes. Domino was working not for universal approval, but for honesty in sound and feeling. The record doesn’t strive to smooth its edges for a white audience; it remains rooted in the rhythms and emotional cadences of Black New Orleans.

Yet in that rootedness, there was rebellion. Domino — through his songwriting partnership with Dave Bartholomew — helped redefine what popular music could be, layering blues, ragtime, and Caribbean-tinged swing into early rock ’n’ roll. “All By Myself” might lack the sweeping sweepstakes of a mass hit, but it laid down one of the foundations: music that speaks from the margins, from the margins’ heart.

In later decades, as rock ’n’ roll exploded globally, the influence of Domino’s understated, piano-driven intimacy would echo in ballads, soul songs, and even early pop-rock slow burners. “All By Myself” stands as one of the quieter — yet no less essential — moments in that lineage.

For listeners today who plug in a vinyl copy of Rock and Rollin’ with Fats Domino, the song offers a different kind of time travel: not to crowded dance floors or wild teenage revelry — but to a small, dimly lit club, a stool before a piano, and a man confessing in low tones that deep down, maybe what he wants most is simply to love someone “all by myself.”