The Anthem of a Generation’s Riot: How a Three-Minute Glam Rock Explosion Defined Rebellion

Long before the stadium-filling anthems of Hair Metal, and just as the dust of the first pop-rock wave settled, there existed a raw, unapologetic energy that crackled with glitter and aggression. That energy belonged to Sweet, and it was perfectly encapsulated in their 1973 thunderbolt of a single: “Hell Raiser.” For those of us who came of age amidst the flared trousers and platform boots of the 1970s, this song wasn’t just another hit; it was a defiant soundtrack to youth, a brief, sharp declaration that the party was just getting started.

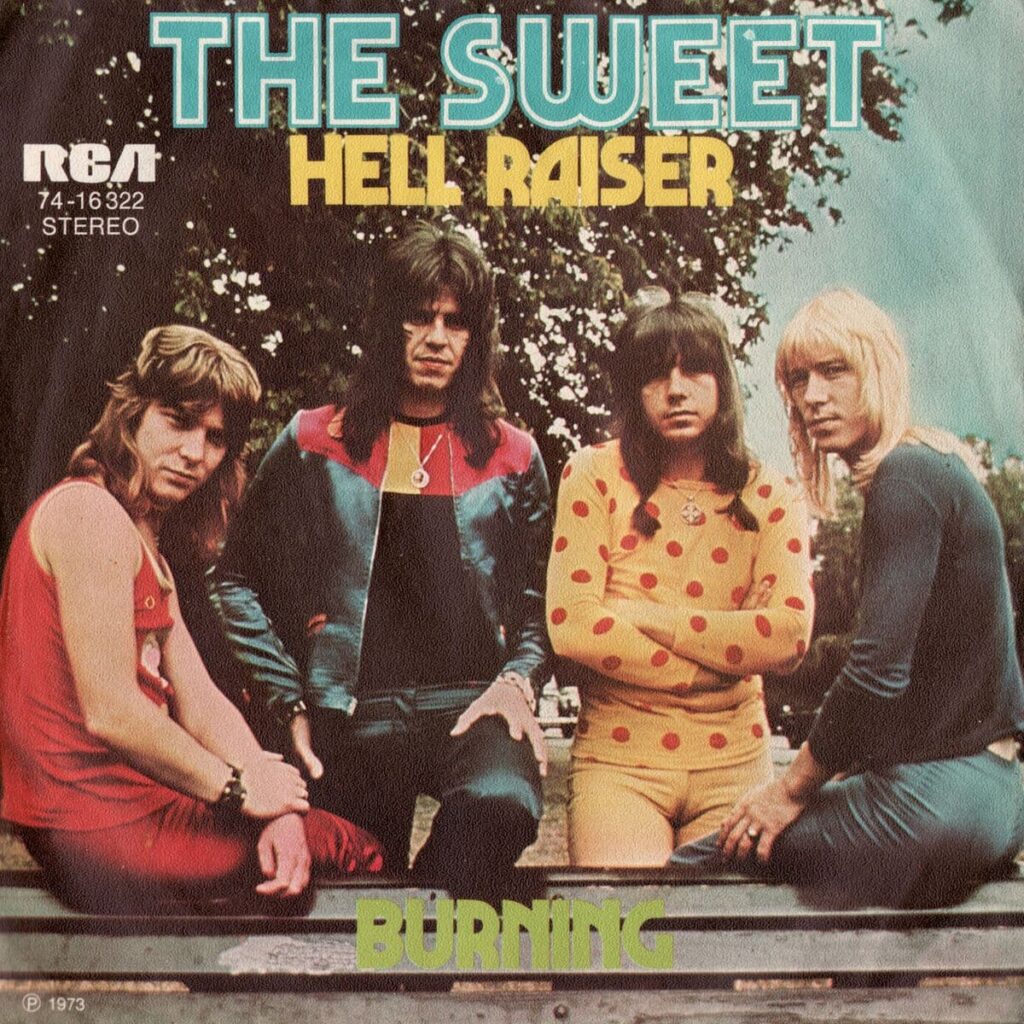

Released on April 27, 1973, on the RCA Victor label, “Hell Raiser” was the band’s thrilling follow-up to their UK chart-topper “Block Buster!” The single was a resounding commercial success, firmly cementing Sweet’s place in the Glam Rock pantheon. It peaked at a solid Number 2 on the UK Official Singles Chart, holding that position for an impressive three weeks. If any record ever felt like a number one—even if it was famously kept off the top by the twin forces of Tony Orlando’s sentimental “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree” and Wizzard’s exuberant “See My Baby Jive”—this was it. Across Europe, its success was even more undeniable: it stormed to Number 1 in Germany and hit Number 2 in Ireland, alongside Top 5 placements in Austria and the Netherlands. This was a continental phenomenon, radiating the irresistible force of four young men who looked like aliens but sounded like a powerhouse hard rock band.

The story behind “Hell Raiser” is inextricably linked to its creators, the legendary songwriting and production team of Mike Chapman and Nicky Chinn. During this period, Sweet—comprising the vocal prowess of Brian Connolly, the virtuosic guitar work of Andy Scott, the solid bass of Steve Priest, and the masterful drumming of Mick Tucker—were still very much in the grip of the Chinn-Chapman machine, produced by Phil Wainman. The writers were brilliant at crafting radio-friendly, catchy rock songs with just enough bite to appeal to the emerging youth culture. While the band yearned to release their self-penned, heavier material, Chapman and Chinn were providing them with singles that simply couldn’t fail. “Hell Raiser” was a purposeful evolution in this commercial direction, a conscious effort to blend the pop sensibilities of earlier hits like “Little Willy” and “Co-Co” with the burgeoning hard rock sound that the band was playing on their album B-sides and live shows. The intent was to deliver pure, unadulterated rock energy with a pop sheen, a formula that defined the very essence of Glam Rock.

The meaning of the song is wonderfully straightforward and speaks to the universal theme of youthful abandon: it is an ode to the quintessential “Hell Raiser,” the trouble-making, charismatic, and irresistible figure of the local music scene. It’s about being drawn to danger, to the person or the event that promises excitement and chaos, regardless of the consequences. The lyrics are a shout-out to the thrilling transgression, celebrating the magnetic pull of someone who lives life at full volume, defying all the staid expectations of respectable society. The sheer power of Brian Connolly’s vocal delivery, backed by those signature, layered Sweet harmonies and Andy Scott’s driving, memorable guitar riff—a riff so powerful it would later be referenced by bands like Mötley Crüe with their track “Kickstart My Heart”—made the message undeniable.

“Hell Raiser” wasn’t just a hit; it was a pivotal moment. It marks a crucial step in the band’s career, straddling the line between their purely bubblegum-glam origins and the heavy, self-penned rock direction they would fully embrace with the Sweet Fanny Adams album a year later. It’s a three-minute, fifteen-second injection of metallic pop perfection that still, all these decades on, retains its intoxicating, rebellious spirit, inviting any listener, regardless of age, to feel the raw energy of 1973 once more. For those of us who were there, turning up the volume on our little transistor radios or smashing the needle onto a pristine vinyl copy, it’s a direct conduit back to the youthful freedom that promised a party around every corner.